Vital Force

boosts immune system function and health of your cells...

Key Ingredients

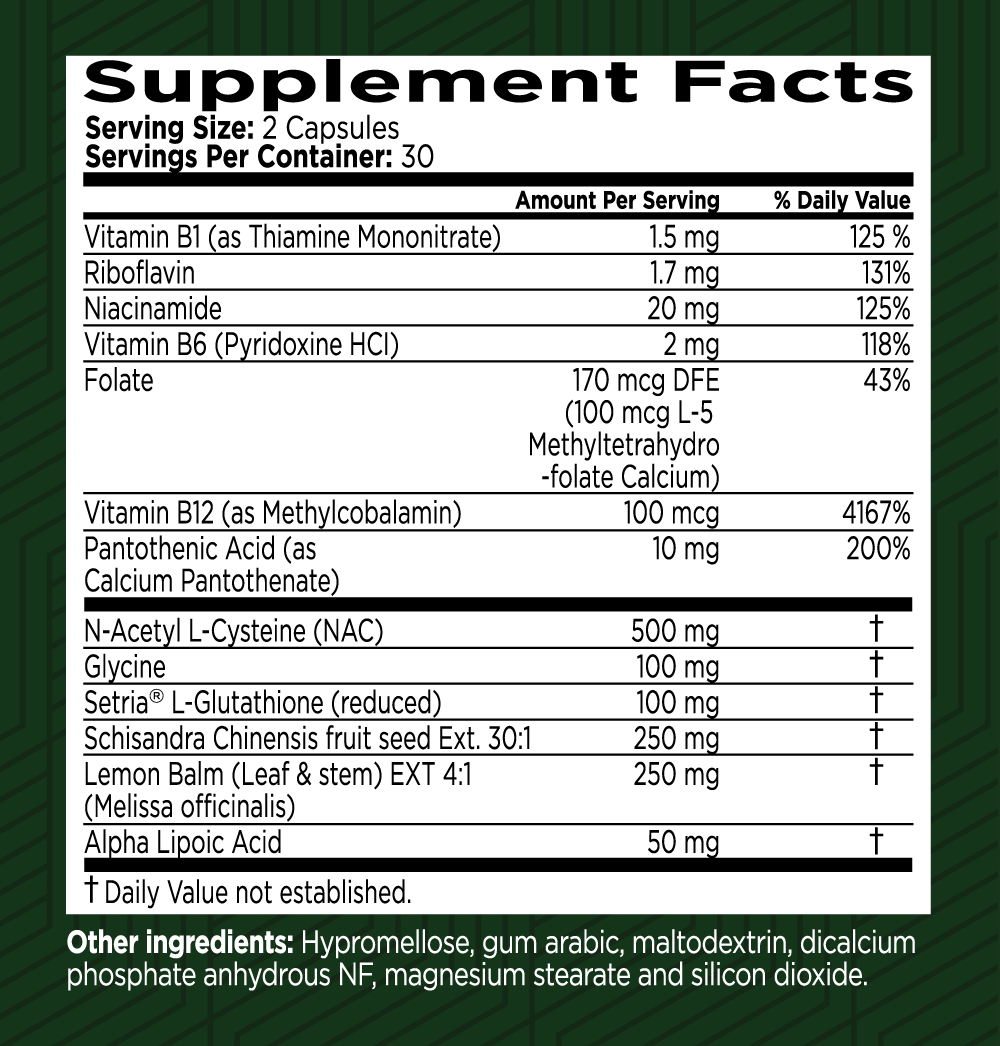

N-Acetyl L-Cysteine (NAC)

A precursor to glutathione, NAC is essential for boosting glutathione levels in the body. It has been shown to enhance lung capacity, support detoxification, build muscle, boost immunity, and improve insulin sensitivity.

Lemon Balm (Leaf & stem) EXT 4:1 (Melissa officinalis)

This herb is known for its ability to elevate glutathione levels and protect against environmental and medical radiation. Lemon balm also supports DNA health and can counteract the effects of stress.

Schisandra Chinensis fruit seed Ext. 30:1

Known as the "glow berry" in Chinese medicine, Schisandra is used for its anti-aging properties. It increases glutathione levels in mitochondria, supporting energy production, brain health, stress reduction, and overall vitality.

Setria® L-Glutathione (reduced)

A bioavailable form of glutathione that supplements the body's natural production. It provides a layer of protection in the gastrointestinal tract and increases glutathione levels in the bloodstream, supporting immune function.

Vitamin B1 (as Thiamine Mononitrate)

Vitamin B1 (as Thiamine Mononitrate) is a crucial supplement for supporting energy production, nerve function, and overall cellular health. By converting food into energy and promoting the proper functioning of the heart, muscles, and nervous system, Vitamin B1 is an essential addition to your daily wellness routine, ensuring optimal health and vitality.

Riboflavin

Riboflavin (Vitamin B2) is a vital supplement that supports energy production, red blood cell formation, and overall cellular health. By participating in essential metabolic reactions and providing antioxidant protection, Riboflavin is an important addition to your daily wellness routine, promoting optimal health and vitality.

Niacinamide

Niacinamide (Vitamin B3) is a versatile supplement that supports energy production, skin health, and overall well-being. By participating in essential metabolic reactions and providing anti-inflammatory benefits, Niacinamide is an important addition to your daily wellness routine, promoting optimal health and vitality.

Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine HCI)

Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine HCl) is a vital supplement that supports numerous bodily functions, including amino acid metabolism, neurotransmitter synthesis, and hemoglobin production. By enhancing cognitive function, mood, and cardiovascular health, Vitamin B6 is an essential addition to your daily wellness routine, promoting optimal health and vitality.

Folate

Folate (L-5-Methyltetrahydrofolate Calcium 70%) is a superior supplement that supports DNA synthesis, cell division, and overall health. By providing a bioavailable form of folate, it ensures optimal absorption and efficacy, promoting cardiovascular health, cognitive function, and prenatal development. Folate is an essential addition to your daily wellness routine, supporting optimal health and vitality.

Vitamin B12 (as Methylcobalamin)

Vitamin B12 (as Methylcobalamin) is a highly bioavailable supplement that supports nerve health, red blood cell formation, and DNA synthesis. By providing the active form of B12, it ensures optimal absorption and efficacy, promoting energy production, cognitive function, and overall well-being. Vitamin B12 is an essential addition to your daily wellness routine, supporting optimal health and vitality.

Pantothenic Acid (as Calcium Pantothenate)

Pantothenic Acid (as Calcium Pantothenate) is a vital supplement that supports energy metabolism, adrenal function, and overall cellular health. By providing a stable and bioavailable form of Vitamin B5, it ensures optimal absorption and effectiveness, promoting healthy skin, hair, and cognitive function. Pantothenic Acid is an essential addition to your daily wellness routine, supporting optimal health and vitality.

Glycine

Glycine is a versatile supplement that supports protein synthesis, neurotransmitter function, and overall health. By enhancing cognitive function, improving sleep quality, and supporting metabolic and joint health, Glycine is an essential addition to your daily wellness routine, promoting optimal health and well-being.

Alpha Lipoic Acid

Alpha Lipoic Acid is a potent antioxidant that supports energy production, metabolic health, and overall well-being. By reducing oxidative stress, enhancing antioxidant regeneration, and improving insulin sensitivity, Alpha Lipoic Acid is a vital addition to your daily wellness routine, promoting optimal health and vitality.

Frequently Asked Questions

Your health is our top priority

Here at Green Valley, we only work with US-based manufacturing facilities that are cGMP (Good Manufacturing Practices) compliant and FDA inspected.

Our products are triple tested by our manufacturers to ensure potency and purity and are stored in our temperature and humidity-controlled warehouse right here in the Shenandoah Valley, Virginia. And we ship directly to your doorstep – we don’t share warehouse space and we don’t hand off your business to a third party to fulfill your order.

Best of all, all Green Valley products come with our 90-day Satisfaction Guarantee. If you are unhappy with the product for any reason, simply call or email our customer support team and return the unused portion of the product within 90 days of your order. We’ll refund every penny of your purchase (less shipping), no questions asked!

Vital Force Customer Reviews

They did a jam up job

They did a jam up job ..the order came as expected, they introduced me to glutathione which seems to help some.

Green Valley Naturals is an excellent company

Green Valley Naturals is an excellent company. I have been using their Brain vitality and vital force and my mind is clearer than it's been in ages. I'm no longer having to stop and figure out where I am and where I'm going. It's chased the cobwebs away. I'm more alert than I've been in a long time. I'm in the process of ordering more. I recommend anybody that has trouble with their memory to try these organic made pills and maybe you will have the same revaluation that I did. Thank you, Terry

I started taking Vital Force 2 months ago

I started taking Vital Force 2 months ago. But only every 2 days or so due to my age and body sensitivity plus I'm a "lite" (half doser). So far, I have more energy and just feel better. Too soon to tell how it's affecting my life. I started feeling results after 2 to 3 doses.